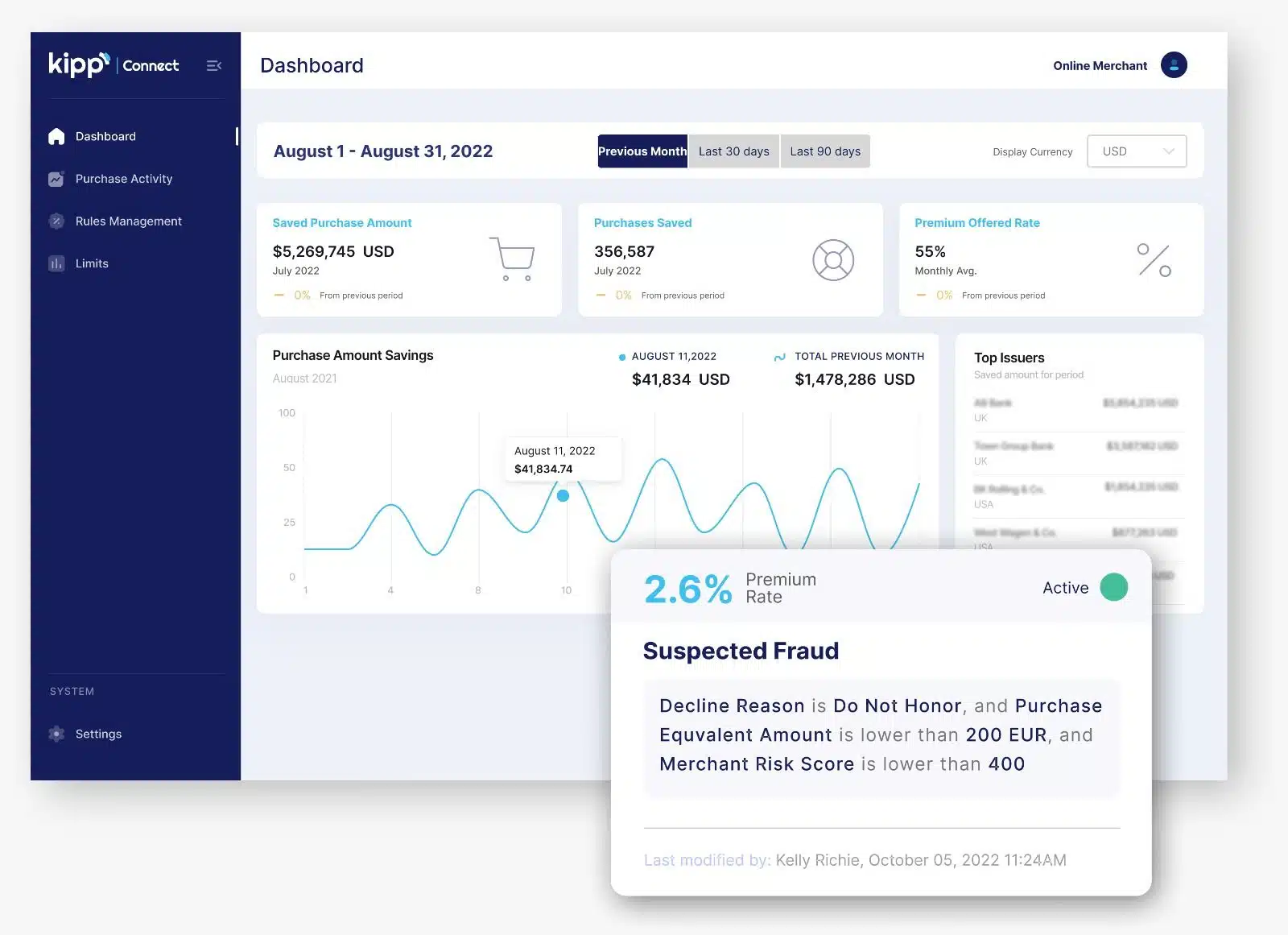

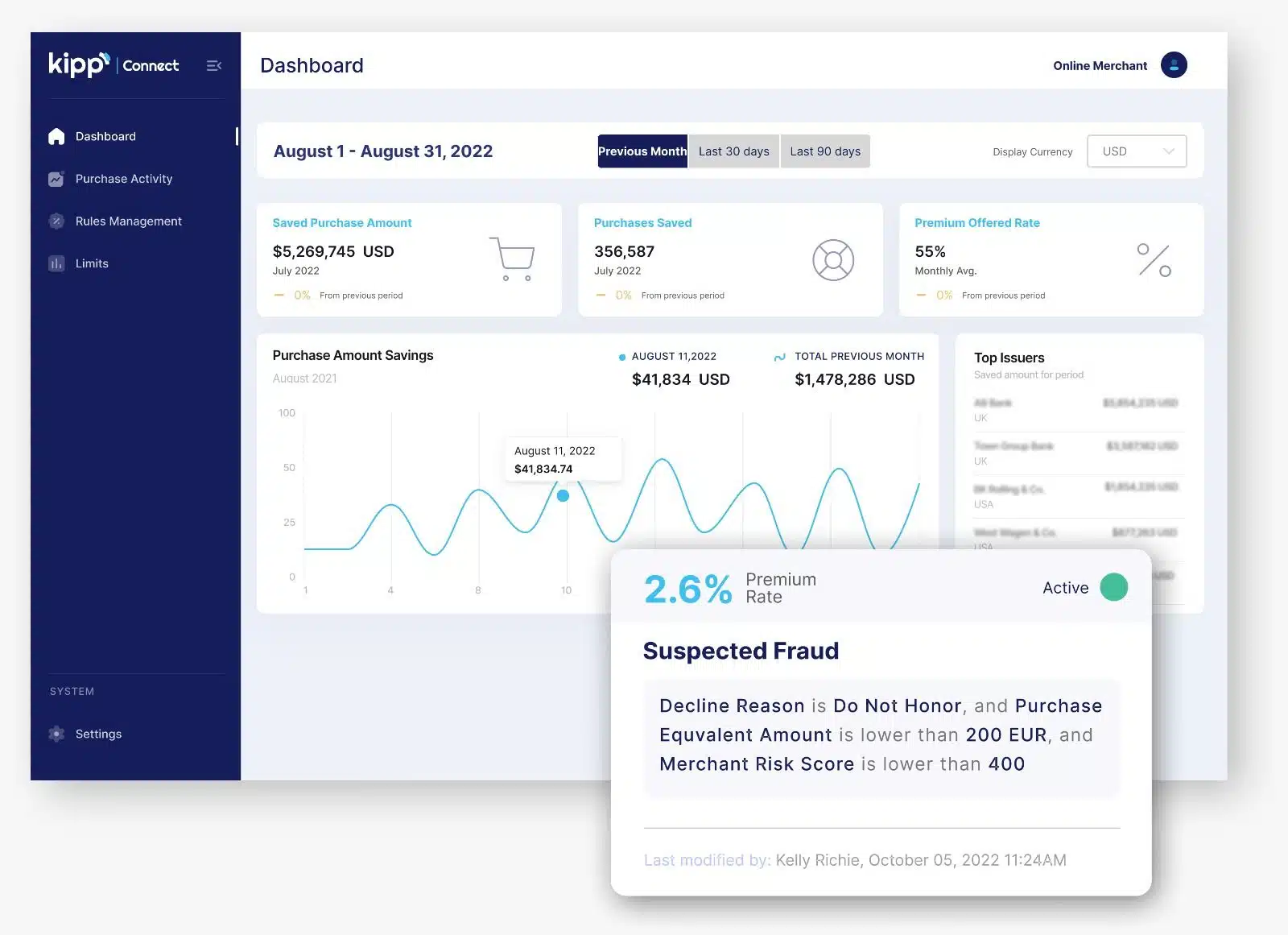

Bank policy

Each bank may have its own preference — based on best practice, its own pattern analysis, or actuarial risk calculations — for specific types of transactions. Even without a complex algorithm, certain red flags can trigger a decline. Some banks become suspicious when a purchase is made overseas, and some take extra precautions for purchases over a large amount, even if it is within the customer’s credit limit. These red flags are unique to each bank and are not made public — as a result, there can be a surprise when a customer suffers the repercussions of raising one.

Insufficient funds

If we consider a credit card purchase as essentially a short-term loan, we understand that the bank has the right to run a “credit check.” And as they have access to the balance of your bank account, it’s easy enough for them to determine that you represent a risk of default on a particular payment.

If only it were that simple.

Using a credit limit or snapshot of today’s balance does not take into account that the customer may have other sources of funds like an expected bonus, a loan from a relative, a sale of stock, or even simply the readiness to pay the interest on payment over a few months. The customer may even have bonds to sell, an inheritance, or funds stored in a savings account in another bank.

Often, unusual purchases are needed in order to fund major life events like a birth, wedding, purchase of a new home, and more. The customer often has a plan to repay the outlay, but, alas, the bank has no way to know.

Technically, it’s possible to call the bank’s credit department and ask for a short-term adjustment to a credit limit, but this can be a lengthy and frustrating process, and many customers instead prefer shifting to a Buy Now Pay Later scheme offered by merchants who are asking for payments over time — without extra fees or interest — rather than everything up front.

One cannot forget that the merchant may have plenty of supporting data to indicate that they are dealing with a reliable customer who pays their bills regularly. But the bank does not have this information; their perspective is restricted to the dollar amount you have at this moment.

Fraud

It’s never a pleasant feeling being told by a bank (especially when you’ve been a customer for years) that they simply don’t trust you. It’s hard not to take it personally, but the reality is that it is frequently a kind of benign fluke: there is a mismatch between your shipping and billing addresses, a device ID is unfamiliar, certain types of products are being ordered in bulk or from overseas, etc.

Let’s accept for a moment that fraud systems deployed by credit card companies do need to be conservative and determine how significant the red flags are; the problem is that they do not have all that much data to work with — they only access purchase history on their own card. They don’t know about a customer’s reliability using other cards or consistent purchases through this (or any other) merchant. They don’t even know if this particular purchase is unusually large for a particular customer, except by comparing it to other purchases made using this card in particular.

In the event that the customer pulls out a competitor’s card and the transaction does go through due to a more relaxed set of algorithmic rules, the original credit card issuer may lose that client and associated revenues.